It was a stormy day at the Brimfield Flea Market last September. So much so a tree fell across my driveway and nearly blocked me out. But I didn’t know that yet. I had a set of early National Geographic maps tucked under my arm that I got for a steal, and couldn’t let a drop of water soil my new treasures, no matter how nominal the cost. There came a gap in the rain so I took advantage of it and moved to a different tent.

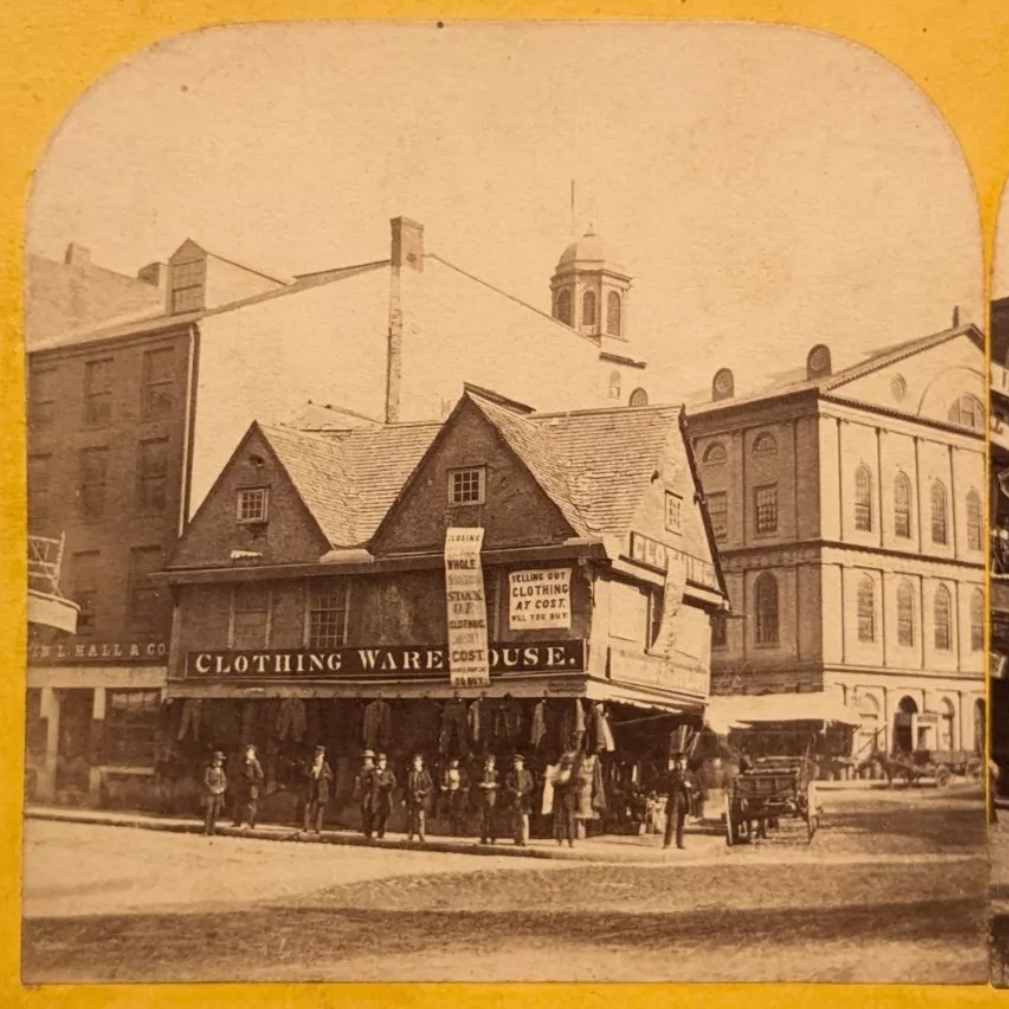

Each dealer had their own white party tent to display their wares. I took shelter in a booth just as the thunder boomed and the rain commenced again. This dealer specialized in post cards. I found the New Hampshire box and pulled out the card you see above. It’s a real photo postcard (RPPC)1 depicting the Tip Top House on Mt. Washington. There are many pictures of this hotel out there, but this one is unlike any other I’ve seen. Scrap wood and miscellaneous materials are strewn about the foreground. Identifiable objects include an AMC trail sign, another sign on top of a barrel saying “Please do not molest woodchucks,” a wheelbarrow, hatchet, window, fire bucket, toolbox, and window shutters.

The scene piqued my curiosity. It’s not everyday you see bric-a-brac outside an upscale hostelry. The card is unused and has no written information, except of course the resident woodchuck population on Mt. Washington. When the rain subsided I bought the card and returned to my car.

Narrowing the date of this postcard was a fun task. First, there are a couple of clues on the back. The stamp box has the letters “AZO” and four upward pointing triangles at each corner, a design used from 1904-1918.2 It is a divided back card, a style used between 1907 and 1915.

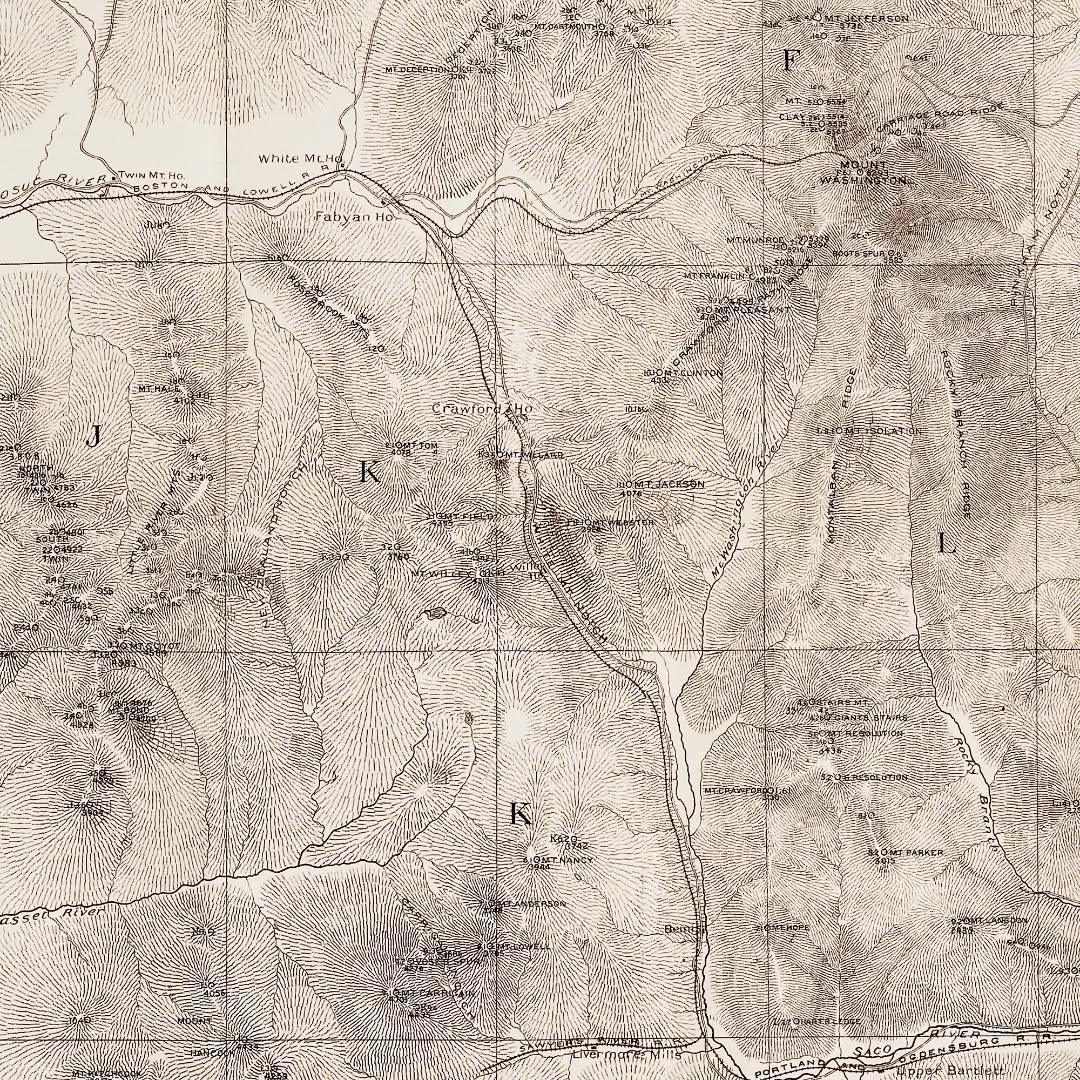

Returning to the photograph, here’s where it gets interesting. There’s a trail sign in the photo listing the Crawford Bridle Path, Boott Spur, and Boulder trails. Boulder presumably refers to the Glen Boulder Trail. According to the AMC White Mountain Guide of 1920, the Boott Spur Trail was constructed in 1900 and Glen Boulder by 1906, so the photo must postdate that, although it does not narrow down the date range any further. The Tip Top House burned on August 29, 1915 and was subsequently rebuilt, but that doesn’t narrow the date either. Ironically, there’s a fire bucket in the foreground.

I continued my search on the AMC Archives website. There was another fire on Mt. Washington June 18, 1908. All the summit buildings burned except the Tip Top House. I found one image of this event with Tip Top House in the background.3 The break in the boardwalk railing in the postcard match that of the AMC photo. It makes sense, too, for a fire bucket to be out after a blaze, not to mention scattered materials and debris. I believe this postcard dates to June 1908!

I’ve seen other photos from the 1908 fire since writing above,4 and the broken railing seems to be the best identifier of photos taken immediately after the disaster.

The photographer is unknown, but possibly Guy Shorey, who sold his own postcards in Gorham, NH. He visited the summit ruins the morning after the fire.5

Footnotes

- Real photo postcards are photographs produced directly on post card stock. Learn more about the medium on Wikipedia. ↩︎

- Playle, David, “How to Identify and Date Real Photo Vintage Postcards,” playle.com, David Playle, https://www.playle.com/realphoto/. ↩︎

- [The summit of Mount Washington, N.H., showing the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1908, with the Tip Top House and the Cog Railway track], June 19, 1908, LS35.03, lantern slide, Appalachian Mountain Club Library & Archvies, AMC Highland Center at Crawford Notch, Bretton Woods, NH, https://outdoors.catalogaccess.com/photos/1585. ↩︎

- Russack, Rick, “Fire on the summit: 101 years ago,” White Mountain History, WhiteMountainHistory.org, https://www.whitemountainhistory.org/fire-on-mt-washington. A better photo of the broken railing is in the gallery at the bottom of the page. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎